.

Transport: Roads

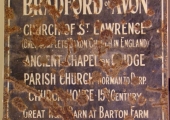

In the Hundred of Bradford on Avon, Wiltshire

.

On a generally muddy river, a band of limestone in its bed provided a firm ‘broad ford’ at Bradford on Avon. It would have been a convenient point for crossing the River Avon from the end of the last glaciation of the Ice Age, about 12,000 year ago. As such, it may have been a focus for seasonal tracks of migrating herds of animals -deer, wild cattle and even mammoth- and the humans who followed them, eventually becoming routes across the area, some perhaps still in use today.

On a generally muddy river, a band of limestone in its bed provided a firm ‘broad ford’ at Bradford on Avon. It would have been a convenient point for crossing the River Avon from the end of the last glaciation of the Ice Age, about 12,000 year ago. As such, it may have been a focus for seasonal tracks of migrating herds of animals -deer, wild cattle and even mammoth- and the humans who followed them, eventually becoming routes across the area, some perhaps still in use today.

The first definite roads were made by the Romans, following the invasion of Britannia in AD43. The earliest was what came to be called the Fosse Way, running diagonally from the English Channel near Axminster, Devon in the SW to the Humber in Lincolnshire in the NE. It passes close to Bradford on Avon at Limpley Stoke and at Bathford. Another road, from Londinium to the spa town of Aquae Sulis, modern Bath, is marked by the straight northern boundary of the Bradford Hundred and of the modern parishes of Atworth and South Wraxall. A road that went southward from Bath to the port at Poole Harbour in Dorset just touches the western point of Limpley Stoke. Minor roads must have connected to small settlements, including the important villas at Atworth and Budbury. There may have been a road that connected Bath with the town of Sorviodunum at Old Sarum near Salisbury, perhaps using the crossing at Bradford. The charter by which King Æthelred II granted the manor of Westwood to his huntsman Leofwine in 983 mentions the stræt (street, from the Latin strata), a word usually used in Saxon times to refer to a Roman road. Its position was on the modern road to Wingfield near Midway Manor (B3109), a road that was called ‘the highway‘ in a deed of 1702 and may follow the line of a Roman way that perhaps joined the Bath-Poole road somewhere near Frome.

After the Romans, many of their roads continued in use, but parts of that from London to Bath partly became a long defensive work called Wansdyke and it mostly went out of use. Saxon roads existed, including one, called a here waie, or army road, that was mentioned in the Bradford Manor charter of 1001, on the border of the modern parishes of Holt and Broughton Gifford.

It is probably safe to say that there were ways leading to places to cross rivers where ‘ford’ is included in their names: Iford (Westwood), Stowford (in Wingfield) and Freshford (Somerset) across the Frome; Stokeford across the Avon between Limpley Stoke and Winsley; Midford in the far west of Limpley Stoke; Bathford (formerly just Ford, Somerset). A place simply called Ford lies on the route from Bradford to South Wraxall and Corsham, where it would cross a brook. Stowford was originally Stanford, suggesting a stony bed, it was perhaps even paved. There was also a ford across the Avon at Monkton in Broughton Gifford and another lower on the river at Staverton, where a limestone band allowed a relatively mud-free passage. A wooden bridge over the Biss that gave Trowbridge (tree bridge) its name was in existence in early times and a bridge over the Avon was recorded in 1415. Medieval bridges replaced the fords at Bradford (12th century), Iford (c1400), Freshford (early 16th century), Staverton (15th century); John Leland noted a bridge at Midford in his travels in c1540; the bridge over the Bybrook at Bathford is dated 1665, but may have replaced a previous one.

Routes must have existed in the middle ages between the town and the villages of the Bradford Hundred. There would have been a need for villagers to get to meetings of courts of the Hundred and the various manors that they were obliged to attend, as well as going to markets and fairs, working in the fields, driving livestock, paying rents and tithes and taking corn to be milled. Some of these routes may have been converted, in part at least, into turnpike roads in the 18th century and to other modern roads, while others persist only as tracks and footpaths, or have disappeared altogether.

Ways would have connected Bradford also to other market towns -especially Bath, Trowbridge, Corsham, Melksham and Frome. Goods that were not produced locally -like iron and other metals and pottery, had to be imported. Wool, and later finished woollen cloth, were exported to London, Salisbury and to ports like Southampton.

Of special importance would have been a route from Bradford to Shaftesbury Abbey for carrying produce, including livestock, to the abbey and for the visits of the Abbey’s bailiff and retinue to Bradford. In 1376 an entire two-storey timber porch was sent, in flat-pack form presumably, along with 600 feet of fencing to Shaftesbury and in 1392 new barn doors were sent to Kilmington and 150 feet of stone ridge tiles was sent for a building at Tisbury. There was also a need for communication with Kelston, the abbey’s other local property, that seems to have been administered from Bradford. It was recorded that in 1383 men and stone were sent from Bradford to Kelston to build an oxhouse for the abbey’s reeve, its chief official there. Although both Bradford and Kelston are on the River Avon, weirs and mills at Avoncliff, Limpley Stoke, Warleigh, Bathampton, Bath and Twerton would have impeded water transport, so presumably they would have gone by road through Bath. Exchanges of flocks of sheep were carried out between Bradford and the Abbey’s manor of Liddington near Swindon. Likewise, there must have been some traffic of goods, livestock and people between the Priory of St Swithun (later Cathedral) at Winchester and its manor of Westwood, between Keynsham Abbey and its property in Wingfield and between the Priory of Monkton Farleigh and its properties in Broughton Gifford, Chippenham and elsewhere. The lords of other great estates also moved produce and animals between their scattered manors; the main sheep-rearing manor of the Hungerfords was at Heytesbury, east of Warminster, from where flocks were driven to other land and must have passed through the Bradford Hundred to their castle at Farleigh Hungerford.

When John Ogilby published Britannia, the first road atlas, in 1675, the only important road that crossed the Hundred of Bradford was that from London to Wells via Devizes. This crossed from Trowbridge in the east at London Bridge to Farleigh Hungerford Bridge in the west. He marked a side road to Bradford from Hilperton, presumably over Staverton Bridge and another from the crossroads on Wingfield Common. Another road was marked to Bath and Bradford just west of Wingfield; this may be what is now a series of footpaths and tracks leading from near Stowford via Westwood.

Generally, the roads were in poor condition, especially in wet winters. Only with the end of the 17th and beginning of the 18th centuries did they start to receive serious improvement with the formation of Turnpike Trusts and the taking in hand of bridges by the County Quarter Sessions.

Today roads are the responsibility of national and local government authorities. Central government, in the form of Highways England, provides the main trunk routes (the A36 Warminster Road is the only one in the Bradford Hundred area) and Wiltshire Council the others.